In the past year, we’ve seen regional rental markets start to ease a bit. They’re still very tight, but things are starting to improve.

Is that a sign that the shift to the regions that we saw during the pandemic is reversing? Is everyone moving back to cities now that they are reopen and people are back in the office?

Unfortunately, we don’t get data on population movements in anything like real time; in fact, we only recently got data for last financial year. That makes it hard to know.

But we can use housing data as a bit of a proxy.

It suggests that, yes, in some regions we’re seeing population move back – particularly in some of the “lifestyle” regions - and housing markets have weakened in these areas as a result.

But in other regions we haven’t seen that reversal. While we aren’t seeing the same strong shift into these regions and housing outperformance that we did during pandemic, we also aren’t seeing signs that internal migration to these regions has slammed into reverse.

People have always, on net, moved from cities to regions; but the flow was much higher during COVID

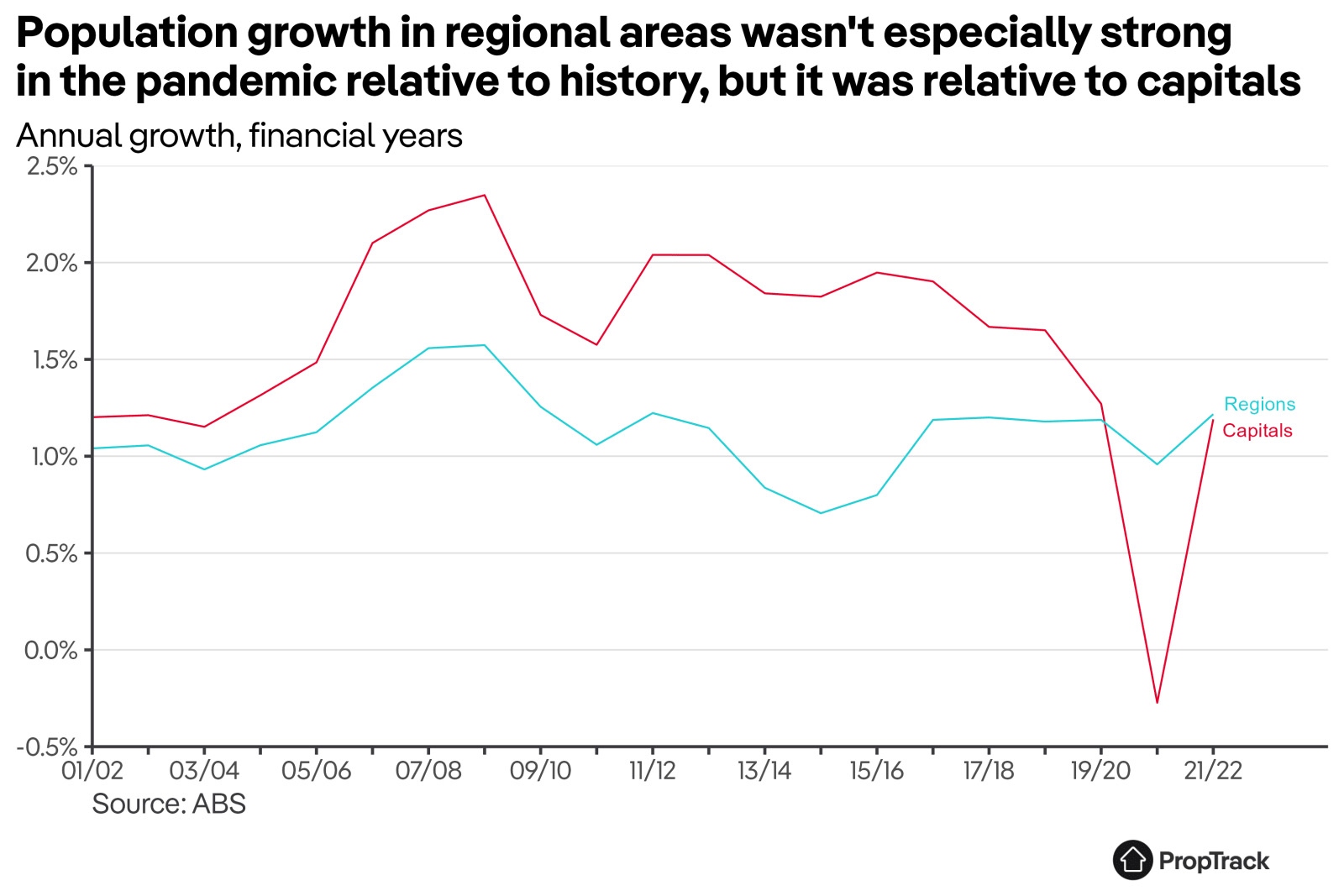

Population growth in regional areas actually wasn’t particularly unusual during the pandemic. If anything, it was a bit lower than has been typical over the past couple of decades.

What was unusual was that regional population growth far exceeded growth in capital cities, a complete reversal of the usual pattern.

This difference in population growth in large part explains the relative performance of regional property markets during COVID. Prices grew substantially faster in regional areas than in capital cities, and rental vacancy rates fell to extremely low levels in mid-2020 and have largely stayed there since.

There were two factors that drove that gap between city and regional population growth.

First: net overseas migration collapsed. That mostly weighed on population growth in capital cities, as recent migrants disproportionately move to capital cities. But it did also weigh on population growth in regional areas, as some migrants move into the regions, but the impact was much smaller.

The second factor was that net internal migration to regional areas surged during the pandemic.

Regional areas normally see some net migration from capital cities, but they saw far more during the pandemic. That larger flow of people from cities to the regions offset the loss of overseas migration in regional areas, and contributed to population falling in capital cities.

The question is: was the surge temporary? Will all those extra people that moved to regional areas now move back to capital cities, sending net migration to regional areas into reverse?

What have we seen since the pandemic?

We don’t have timely data, but we can see from the above chart that net migration to the regions was still strong in 2021/22. That’s partly post-pandemic, but certainly not entirely.

And it is also very dated at this point. The fall in prices and improvement in vacancy rates in regional markets mostly happened after the 2021/22 financial year: prices regionally only began falling in May 2022.

In lieu of population data, we can use timely housing market data to get a sense of if people are moving back.

In particular, we can look at what has happened to home prices and rental vacancy rates.

Prices can give us a sense of demand from homebuyers - if we’re seeing a reverse in population flows, that would put downward pressure on home prices.

Similarly, increasing rental vacancy rates could be an indication that renters are moving out, and freeing up rental stock.

In particular, housing markets in some of the “lifestyle” regions in NSW and Victoria that were popular during the pandemic have underperformed over the past year.

Richmond-Tweed (home to Byron Bay), the Central Coast, Mornington Peninsula, the Illawarra and Southern Highlands, and to some extent Hobart have all been among the worst-performing housing markets. They have seen larger increases in rental vacancy rates, and have seen prices fall by more than the national average.

Those outcomes – softer rental markets and falling prices – are consistent with an at least partial reversal in the trend of people moving from the cities to the regions.

But this story is not writ large across regional Australia.

Regional WA and SA have not even seen home prices fall, and rentals markets have remained tight, with little sign of improving.

The same is true for much of regional Queensland, including the Gold and Sunshine Coasts, where housing markets have softened, but not by as much as in some of those worse-performing markets.

Similarly, regional centres in Victoria and New South Wales - like Geelong, Ballarat, Bendigo and Newcastle - have also held up fairly well. Prices have fallen, and rental markets have eased a little; but they haven’t seen the same pullback as some of those pandemic “lifestyle” regions.

What does this mean for the regions?

While we won’t know for sure until we get population data, housing market data suggests some of the shift to the regions was temporary and is starting to unwind - particularly in places like Byron Bay.

But, at least so far, some of the shift to the regions seems to be permanent. Some of the population that moved during the pandemic is staying. And this seems particularly true in larger regional centres, and in Queensland, WA, and SA.

[1] CBA and the Regional Australia Institute publish a measure based on CBA customer data in their Regional Movers Index. It shows that, through to the March quarter 2023, net migration to the regions is not as strong as it was during the pandemic but it still broadly in line with its pre-pandemic level. That is, it does not suggest a big reversal in net migration, much like the housing data discussed below.

[2] Falling prices is not sufficient to show changes in population; we need to see prices falling by more than average. Prices across Australia have fallen as interest rates have risen, so a decline in prices doesn’t necessarily indicate a shift in population flows; but a greater-than-average decline in prices might.

Share This Article

Previous Articles

- November 2024 1

- October 2024 1

- August 2024 1

- July 2024 1

- June 2024 1

- May 2024 3

- April 2024 2

- March 2024 1

- February 2024 1

- November 2023 1

- October 2023 1

- September 2023 1

- August 2023 1

- July 2023 1

- June 2023 1

- May 2023 2

- April 2023 1

- March 2023 1

- February 2023 1

- January 2023 1

- December 2022 1

- November 2022 3

- October 2022 1

- September 2022 2

- August 2022 1

- July 2022 4

- June 2022 3

- May 2022 2

- April 2022 1

- March 2022 1

- February 2022 1

- January 2022 1

- October 2021 1

- September 2021 4

- August 2021 1

- July 2021 2

- May 2021 1

- April 2021 2

- March 2021 2

- February 2021 1

- January 2021 2

- December 2020 2

- November 2020 2

- October 2020 2

- August 2020 1

- May 2020 2

- April 2020 2

- November 2019 1

- October 2019 1

- August 2019 1

- July 2019 1

- June 2019 1

- May 2019 1

- February 2019 1

- January 2019 1

- October 2018 1

- September 2018 1

- July 2018 2

- June 2018 2

- May 2018 1

- April 2018 2

- March 2018 3

- January 2018 1

- December 2017 3

- November 2017 1

- October 2017 1

- August 2017 1

- July 2017 1

- June 2017 5

- May 2017 31

- April 2017 30

- March 2017 32

- February 2017 28

- January 2017 31

- December 2016 31

- November 2016 29

- October 2016 30

- September 2016 30

- August 2016 26